Subtitled “A Story of the KKK,” this is another response by African American filmmaker Oscar Micheaux to the glorification of that organization by the likes of D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation” and a reminder that some folks knew, even then, how objectionable that was. While it may be seen as polemical, this movie is a testament to the work of minorities in American cinema since the very first years.

The movie begins with the death of an “old prospector,” and the emigration of his young, light-skinned granddaughter Evon (Iris Hall) to “Oristown” which is located somewhere in the Northwest. The proprietor of the local inn is Driscoll (Lawrence Chenault) a man of mixed racial background who discriminates the more viciously against Blacks because of it. We see in a flashback how he lost the love of a white woman when she saw his mother and realized he was not pure white. He tells Evon and a Black traveling salesman (E.G. Tatum) that they have to sleep in the barn because the inn is full. That night, there is a terrible rainstorm and both are discomforted, but Evon flees in terror when she sees the man grimacing in the dark at her, evidently having thought she was alone in the place. She spends a wretched night wandering in the rain, but the next day she meets Hugh Van Allen (Walker Thompson), who is the neighbor of her grandfather’s cabin. He takes pity on her, gives her some food and takes her back to her new home, allowing her to nap in his cart on the way. When he helps her move in, he leaves her with a gun, telling her to shoot twice if she needs assistance of any kind.

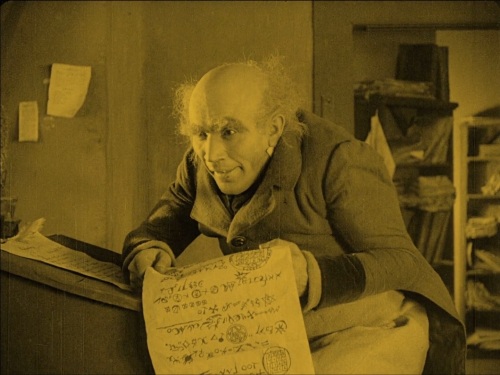

At this point in the movie, the villain, a white man named August Barr (Louis Dean), is introduced. He is assisted by an Indian “fakir” called Tugi (Leigh Whipper) and, of course Driscoll, the “mulatto” from the hotel. They buy stolen horses from some bandits and manage to sell them to Hugh, who is honest enough to return them to their rightful owner when challenged. Their bigger plan, however, is to find out where Evon’s grandfather hid documents in Evon’s cabin (from the footage and intertitles on the existing print, it’s unclear what is so valuable about these documents at this point in the film). When their accomplice sneaks into Evon’s cabin at night, she shrieks so loud that Hugh comes running, although she didn’t use the signal, and the man runs back to their “hideout” in the woods. Hugh now tracks down the former hotel manager at the saloon, and the two brawl over the stolen horses. Hugh wins fair and square, of course, but now the villain has another reason to have it in for Hugh, and vows revenge as he departs. Evon finds work in the field of her new cabin to be difficult, and goes for help to Hugh, who digs a hole for her in return for coffee and a meal. A mail carrier drops an important document, and Driscoll discovers it on a run to check the mail. He learns that it demonstrates the value of Hugh Van Allen’s land. The trio plot to frighten him if he refuses to sell to them. Meanwhile, Driscoll’s mother shows up and immediately moves in with Evon, the one nice person in town.

When Hugh refuses to sell, the villains hire Bill Stanton, “who knows how to make people do what they don’t want to.” He comes up with a plan to terrorize Hugh by making him believe he has been targeted by the KKK. This is portrayed on the screen by showing a single robed-and-hooded rider on horseback bearing a torch and charging toward the camera in a black background, the white of the robes and sparks from the torch popping out in contrast to the Stygian darkness. After the meeting, Hugh starts to get threatening letters from “The Knights of the Black Cross” who tell him to “watch out for your life” if he does not sell out and leave town. A final letter comes while he is out of town and Stanton rallies the conspirators to dress up and ride to finally terrorize him away from the property. Driscoll tries to back out of being the lead rider, telling Barr he will be “somewhere in the vicinity.” Barr’s wife gives the alarm to Evon and Driscoll’s mother, and Evon rides off seeking help. A strange sequence follows in which we see many hooded figures now riding through the night while Evon rides through the woods in daylight in intercut scenes.

Unfortunately, a substantial amount of footage is missing from the surviving print that prevents us from seeing the climax, in which “a colored man with bricks” evidently fights off the Klan riders and the conspiracy is broken. We get to see the oil fields established on Van Allen’s old land, and the large office Hugh now works from. He greets Evon there, and finally realizes that she is also African American, and therefore marriageable to him. The two embrace at last as Abraham, now in the garb of a traveling salesman, briefly looks in at them in a comic moment as the curtain falls.

It’s a shame that we miss out on what is probably the big “action sequence” of the movie, but there is enough here to see what Micheaux was doing with the story. Here, the KKK is depicted, not as a historical organization defending the Old South against Carpetbaggers and Scalawags, nor as some “Klan revisionists” might have it today, as a populist organization on a moral crusade for Protestant values, but as linked to corruption and dishonesty in its very nature. This depiction might even seem to be a critique of the link between white supremacy and capitalism, but for the fact that Hugh is able to be a successful “oil king” in the final reel, implying that Micheaux and his audience accepted egalitarian ideas about equality in the “American Dream” so long as African Americans were not cheated out of their heritage by dishonest whites and white allies. You’d think at least some would have questioned this – after all, how many Black millionaires could they name? And perhaps some did, but we see no sign of a deeper critique here.

It’s also interesting that the relationship between Evon and Hugh is dependent on his realizing that she is Black. This is not because Hugh would refuse to date a white woman, but because he fears any white woman would reject him. This parallels Driscoll’s rejection by the white woman when she sees his mother in the flashback at the beginning of the film. Micheaux points out the pain of this rejection twice, but again does not use it as a means to challenge the racial order directly. It’s possible that this kind of criticism (and that suggested above) would have insured censorship that would have prevented the movie from being seen by the audiences he made it for (mostly African Americans living in segregated cities). Possibly by raising the issue, Micheaux made it possible for audiences “in the know” to carry the conversation forward where he wouldn’t have been allowed to go.

At any rate, this movie is one of the stronger surviving examples of “race film” from the era, and is more complete, and more watchable, than many other such examples. Certainly worth a look for those interested in the period.

Director: Oscar Micheaux

Camera: Unknown

Starring: Iris Hall, Walker Thompson, Lawrence Chenault, Louis Dean, Leigh Whipper, E.G. Tatum

Run Time: 58 minutes (surviving)

You can watch it for free: here (no music) or here (with music).